Welcome to this month’s update to what’s in the night sky for November.

In the Elan Valley International Dark Sky Park, darkness falls even earlier this month – 6.40pm at the beginning of the month and 6.10pm at the end.

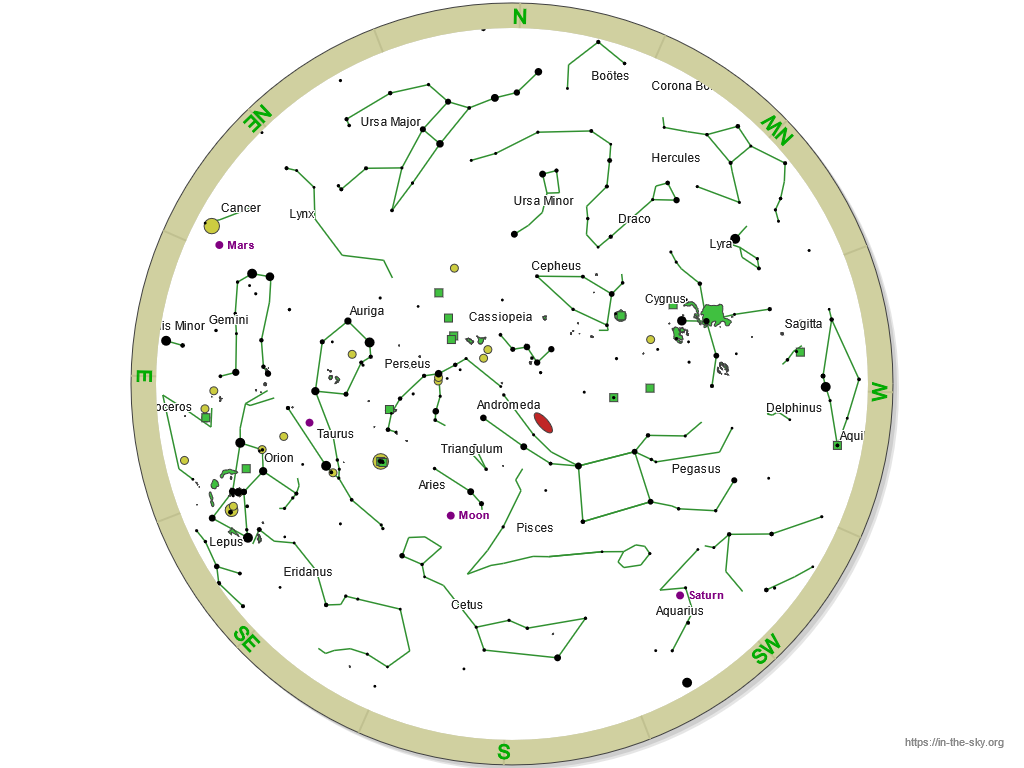

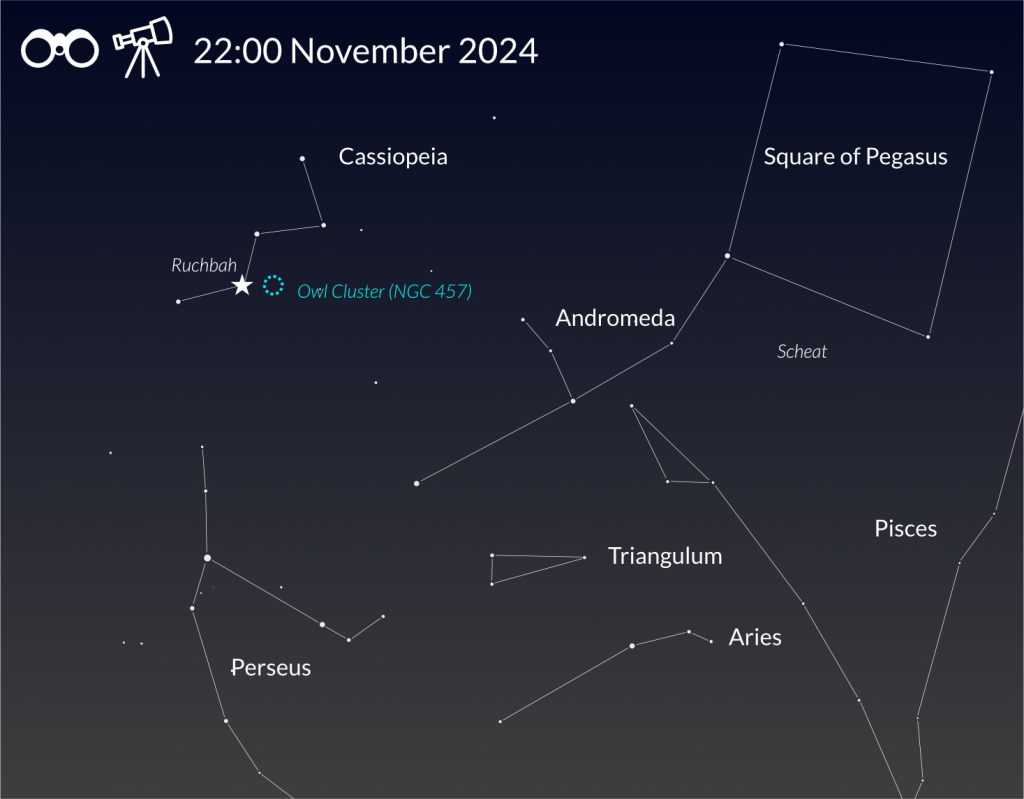

At 10pm, the constellations that are dominant in the southern night sky during November are Pegasus, Andromeda, Triangulum, Pisces and Aries.

Perseus, Auriga and Taurus are well placed, Cygnus and Draco still high in the western sky. The summer constellations of Sagitta, Lyra and Hercules set on the western horizon and the winter constellations of Orion, Gemini and Monoceros rise in the east. Ursa Major, although circumpolar, lies low on the Northern Horizon, making this bright constellation a good landscape astro-photography subject.

Aquarius and the faint low-lying constellation of Capricornus. Cepheus is well-placed. The summer constellations of Hercules, Aquila, Sagittarius and Lyra move westwards and in the east, the winter constellations of Auriga and Taurus begin to rise.

The New Moon falls on 1st November and the Full Moon on 15th November.

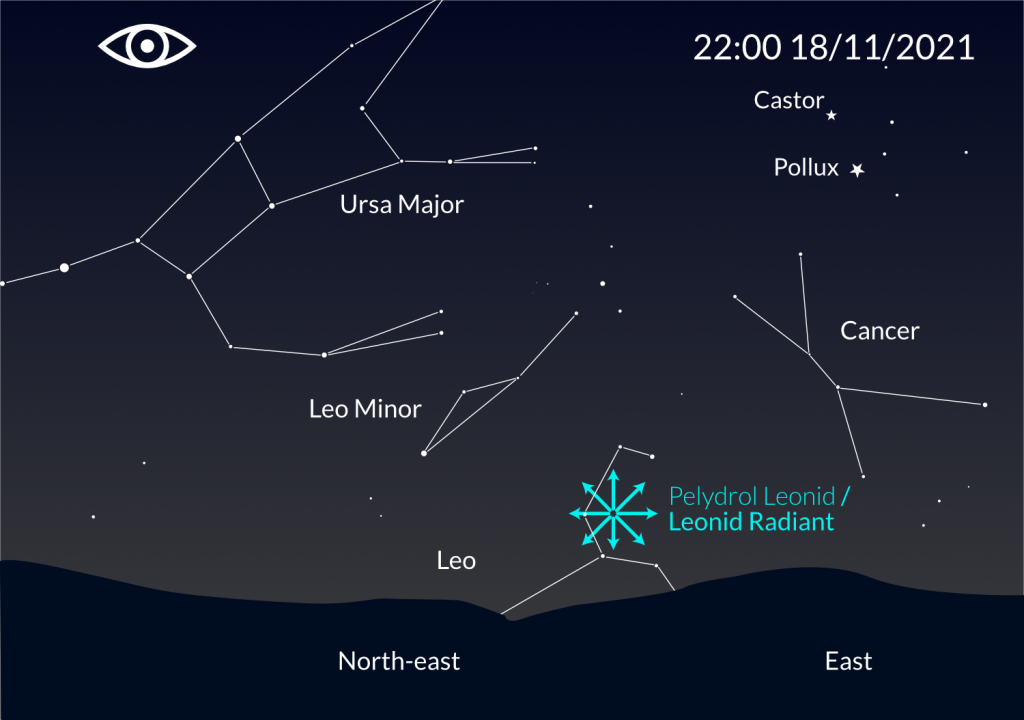

Leonids Meteor Shower

The Leonid Meteor Shower is active from 6th – 30th November and peaks on the night of 18th November, with 15 meteors per hour (ZHR). The point from which the meteors appear is called a radiant and is located in the Constellation of Leo.

As the peak occurs a few days after the Full Moon, you will only be able to see the very bright ones this year, which travel fast and leave long trains.

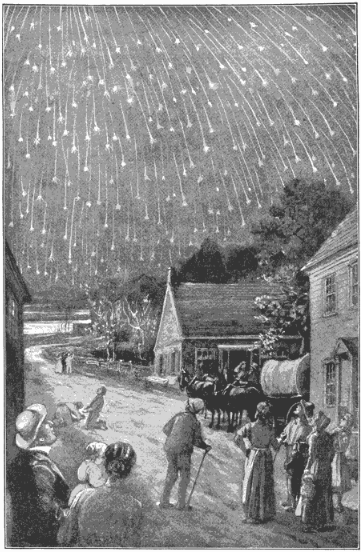

This meteor shower has an interesting cycle: every 33 years the ZHR increases dramatically as there is an outburst and often there can be many hundreds of meteors per hour. The last such storms were 1799, 1833, 1866, 1966 and 1999-2001. The 1833 storm was notable as 3000 meteors per hour was seen by terrified spectators:

“On the night of November 12-13, 1833, a tempest of falling stars broke over the Earth… The sky was scored in every direction with shining tracks and illuminated with majestic fireballs. At Boston, the frequency of meteors was estimated to be about half that of flakes of snow in an average snowstorm. Their numbers… were quite beyond counting; but as it waned, a reckoning was attempted, from which it was computed, on the basis of that much-diminished rate, that 240,000 must have been visible during the nine hours they continued to fall.” – Agnes Clerke’s, Victorian Astronomy Writer

Figure 1: a 19th century woodcut with an impression of the spectacular November 13, 1833 Leonid storm. Courtesy Seventh-Day Adventist Church. Early settlers look up in amazement at a sky filled with shooting stars.

Our next Leonid ‘outburst’ is thought to be in around ten years’ time so let’s hope it’s a good one!

The Planets

This time of year, Jupiter and Saturn are well placed and are worth a study through telescopes.

Saturn is well-placed in the south-west and Jupiter rises in the south-eastern sky at 6.30pm.

If you have never seen a shadow on the face of a gas giant, on 4th November, train your telescopes on Saturn when the mighty moon Titan’s shadow will transit across it between 21.05 and 22:50 – you may notice a slight notch on the edge of Saturn. There will be another opportunity to see this on 20th November between 19:42-22:49, where Titan’s shadow look like a black blob moving across Saturn’s face.

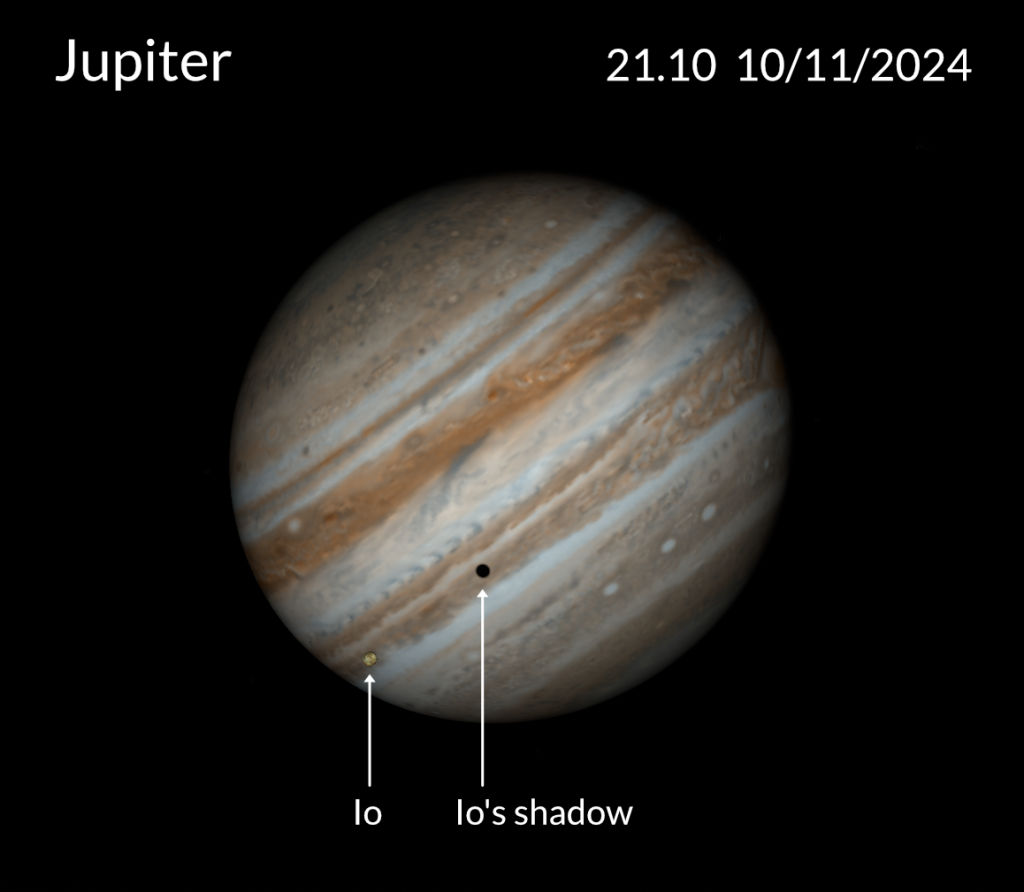

Shadow transits also occur on Jupiter on a regular basis. One to look out for is on 10th November, where you can see the shadow of Io pass across the surface of Jupiter, starting at 20:20 and finishing at 22:33.

Venus will appear low in the South-western sky after sunset.

Mars is a well-placed planet this month, rising in the north-east at 21:10.

The Owl Cluster

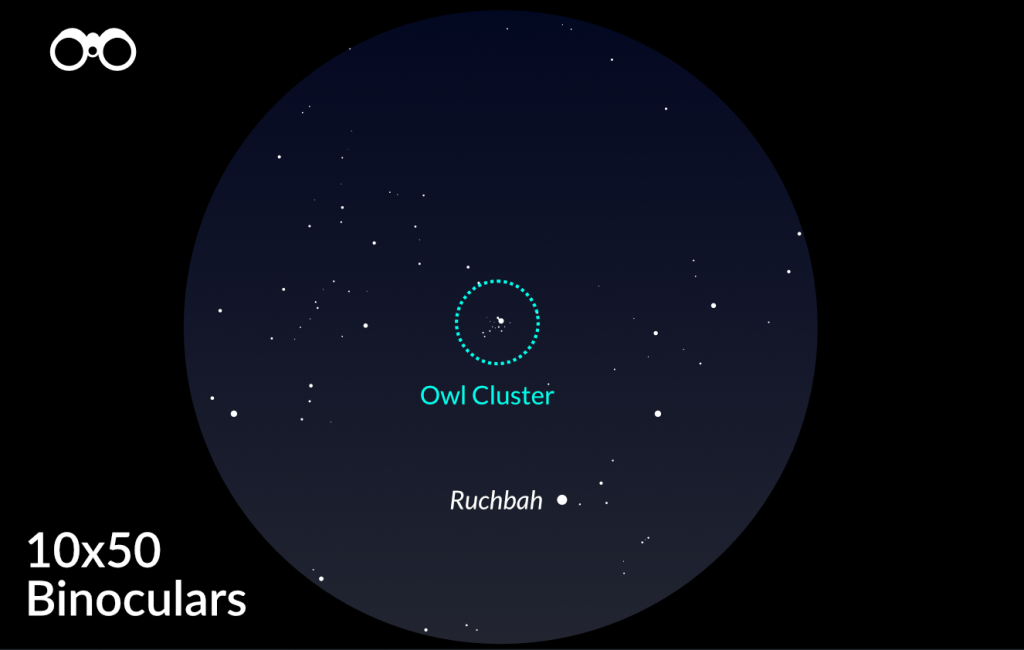

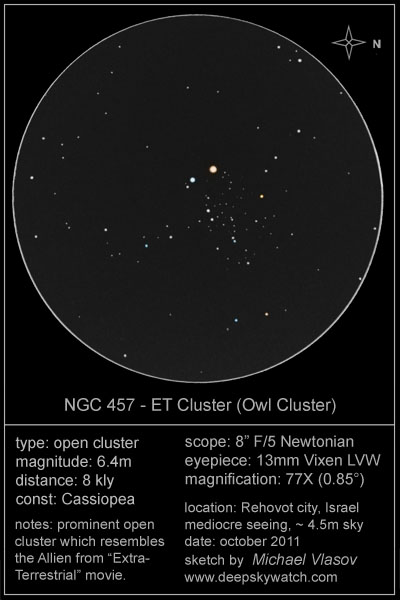

The constellation of Cassiopeia contains some lovely open clusters, all of which can be seen with 10×50 binoculars. One we can recommend you look for this month is the Owl Cluster (NGC 457).

Through 10×50 binoculars, you will be able to see the two bright ‘eyes’ of the cluster and a line of stars perpendicular to the eyes. If you have larger binoculars, the body of the owl becomes more apparent and ‘wings’ can be seen.

Through telescopes, the owl shape takes form and looks stunning. It is also known as the ET cluster because of its resemblance to the alien character from the well-known science fiction film from the 1980s.

Discovered by William Herschel, you can find it for yourself by locating the star Ruchbah. Looking at that star, raise your binoculars to your eyes and scan the immediate area until the cluster comes into view.

Credit: Michael Vlasov from www.deepskywatch.com

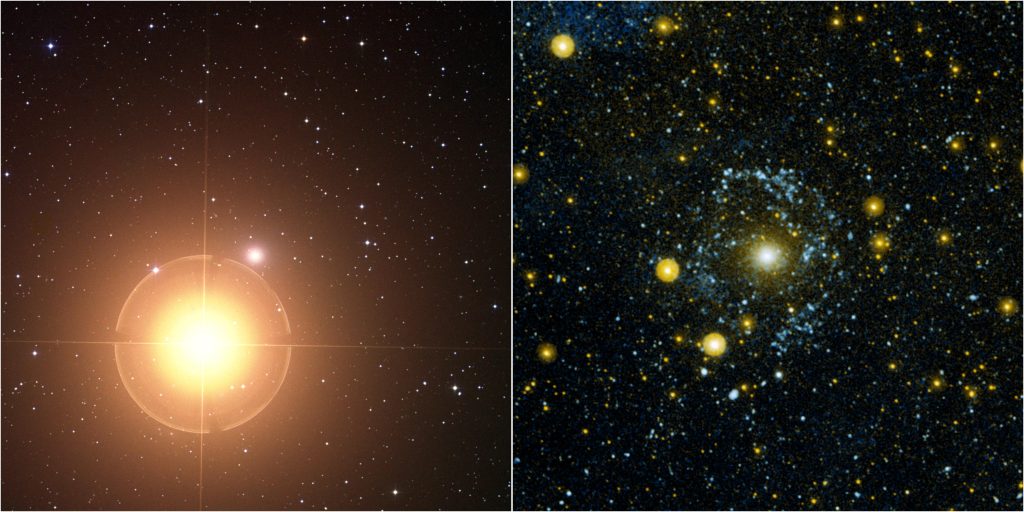

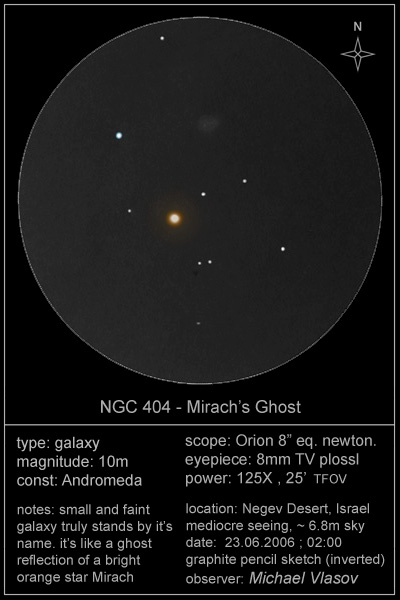

Mirach’s Ghost

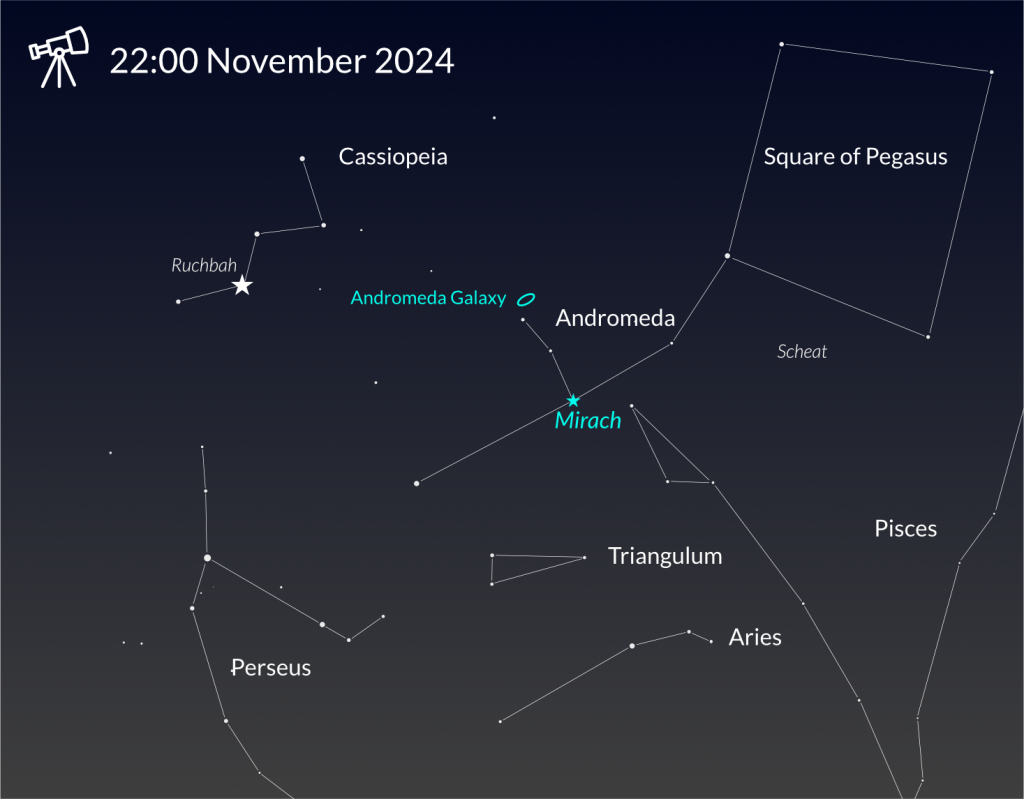

If you have a small telescope, you can look for a fascinating companion to a star whilst you are in the Andromeda/Pegasus region.

To find it, look for the Square of Pegasus and its top left-hand star. Count two stars to the left and that second star is Mirach. The way to tell it’s the right star is to look for two stars that are directly above it, and a fuzzy object which is the Andromeda Galaxy.

Train your telescope on the star Mirach and use your averted vision to look for a ghostly companion which lies close to the star.

NGC 404 is a galaxy which lies 11 million light years from Earth. The reason why it looks dim through telescopes is that Mirach’s brightness dims our views of this galaxy. Even though they appear close to each other here on Earth, there is around 10,999,800 light years distance between them!

The first image to the right shows Mirach and NGC 404 – a galaxy that is lenticular in shape and does not have any spiral arms. It was also thought to be very old and low in star production until the GALEX (NASA Galaxy Evolution Explorer) project deployed a ultraviolet-sensitive telescope to reveal a gas ring and a number of young, hot stars. New studies have revealed that this new star formation was a result of NGC 404 colliding with a neighbouring galaxy long ago

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech